Repair, Regenerate, or Replace? The Orthopaedic Tissue Options

Hear From Our Patients

Skier avoids knee replacement with BioKneeWe are now in the Anabolic Era of sports medicine, where we stimulate natural healing rather than remove tissues and hope for the best. But which to do: repair the injured part, regenerate it, or replace it? Here are a few of the options for the knee:

The Meniscus

Once torn, the meniscus rarely self-heals. The tissues are under compression and shear as the knee joint femur moves on top of the tibial plateau. When the torn edges of the meniscus separate, the forces on the tibia increase, leading to pain and instability. Our preference is to repair every tear that has healthy tissue and for which a stable repair can be predicted. We now have the techniques to stimulate bleeding into all the tissue—a critical part of the body’s healing process—and can augment that process with growth factors and cells.

The meniscus can be regenerated when we have collagen scaffolds to support regeneration. These are currently off the market, but will return.

We replace the meniscus with a donor (allograft) meniscus when sections of it are missing because we have learned, over time and painfully, that even a relatively small section of missing meniscus leads to painful arthritis.

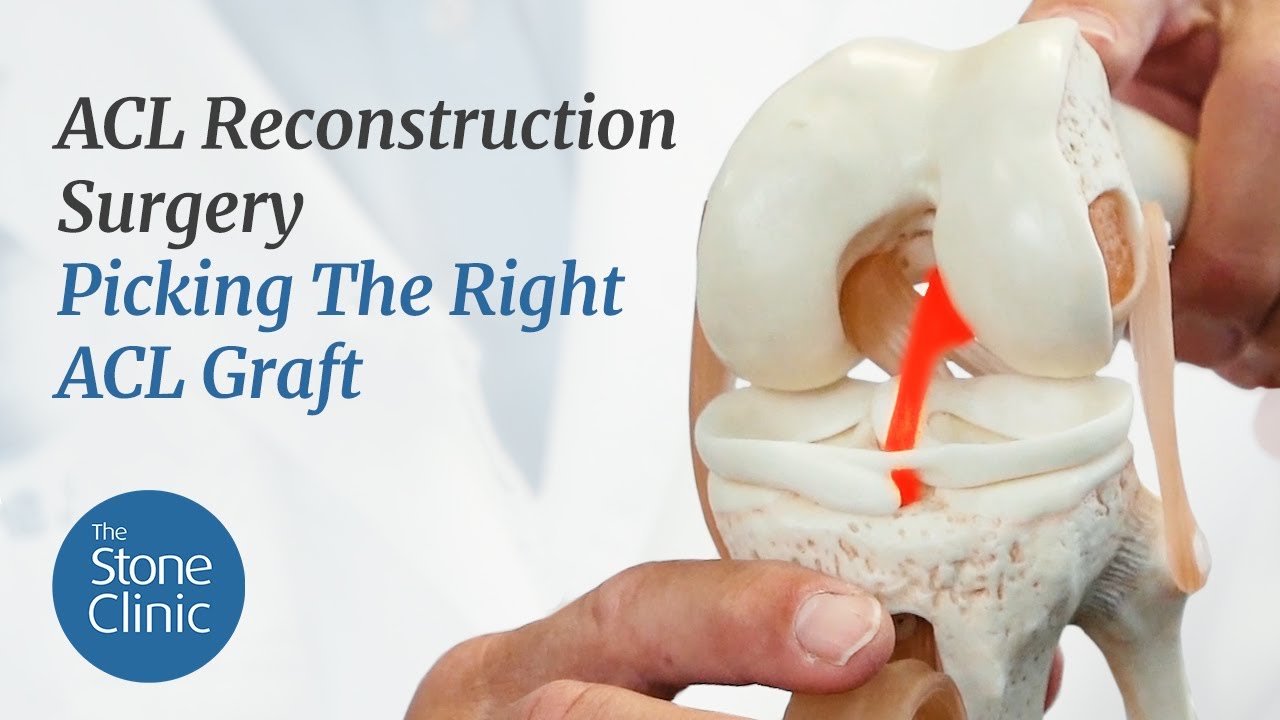

The ACL

A torn ACL does heal on its own. Whether or not the healing leads to a stable knee, however, is the question. Most tears completely rupture the fibers within the structure — like strands in a rope — and even though the top may heal to the surrounding tissue, the knee joint is left unstable.

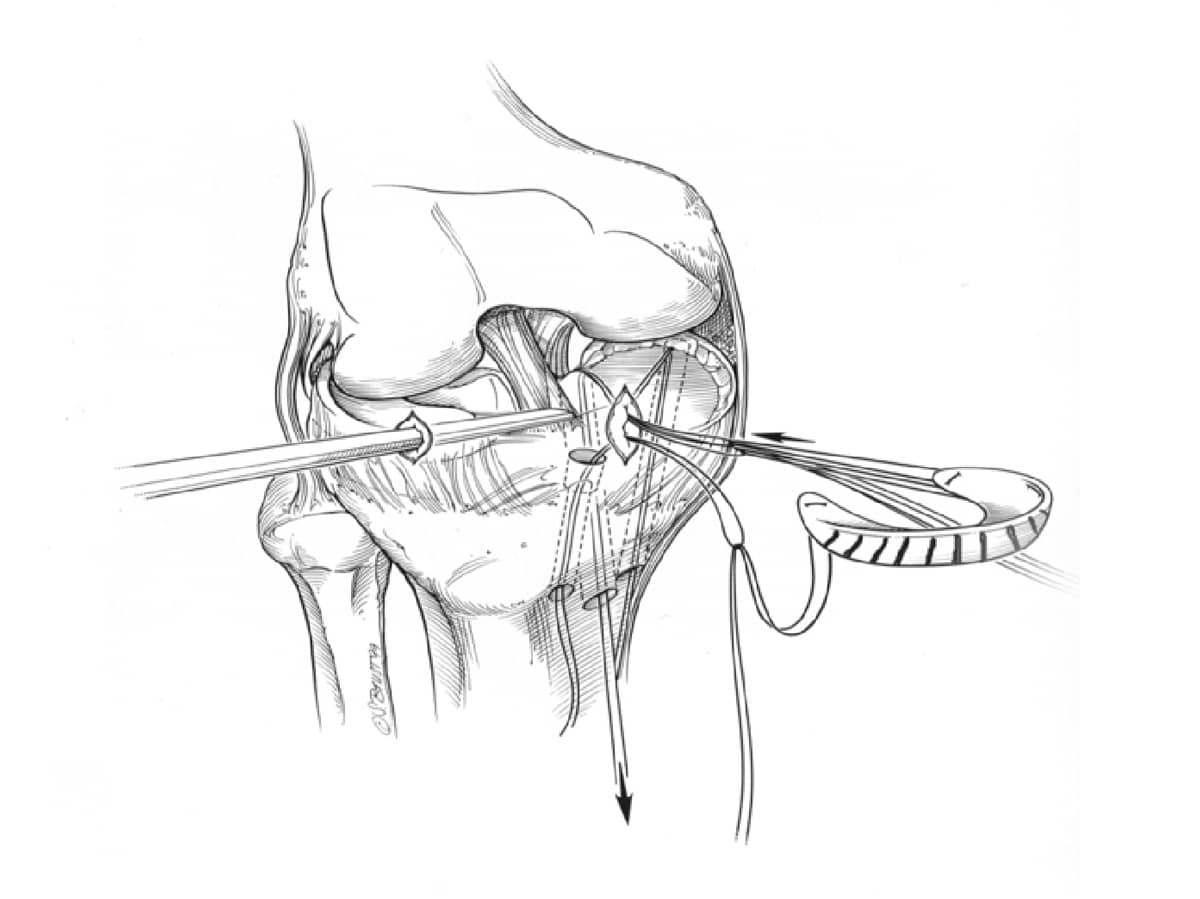

When the tears are near the origin of the ligament or at the bony insertion on the tibia, we repair the tissue back to the bone and protect the tear with an extra articular reconstruction, as this dramatically reduces the likelihood of another tear.

When the ligament is significantly torn, we replace the ACL with donor tissue. Our bias is to use donor quadriceps tendon long enough to replace the ligament and be wrapped around the outside of the knee as an extra articular reconstruction. Other surgeons prefer to use the patient’s own tissue. Our results have been about equal, so we see no reason to weaken one part of the knee to help another.

No artificial materials have been successful at replacing the meniscus. The current trend to augment ACL reconstruction and repair with artificial bands (commercially inspired internal braces) has failed miserably due to “stress shielding” of the replaced tissue: if the tissue doesn’t experience the normal stress of loading, the collagen fibers formed during healing become a disorganized, weak scar rather than a normal ligament.

Cartilage

The articular cartilage covers the ends of all joints and rarely heals well on its own after significant injury.

Repair of the articular cartilage has been shown in multi-decade follow-up studies using our preferred technique of articular cartilage paste grafting. This technique is being upgraded with hydrogels, growth factors, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in a grant from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) to the Stone Research Foundation.

Regeneration of the articular cartilage using meshes (MACI), donor cartilage allografts (Cartiform), and osteochondral grafts (OATS) is becoming more popular as the devastating outcomes of cartilage injuries become more apparent.

Replacement of the cartilage with shell grafts, allografts, and OATS-like procedures is an effort to immediately provide an intact cartilage surface and bone structure to damaged areas of the joint. These have worked well in isolated chondral defects in healthy knees. Once arthritis sets in, however, the degradative enzymes in the joint and the deformities of the surfaces do not lend themselves well to the round replacement plugs. Some success has definitely been achieved, and more will be once the entire joint is addressed. This will entail both cartilage restoration and underlying bone reformation, using the biologic therapies now being developed to induce native stem cell migration to the joint.

Replacement of the cartilage and bone with bionic surfaces of metal caps, and partial and total knee replacements (without cement), remains the final solution for many damaged joints too far along for biologic restoration. Fortunately, these bionic joints are returning people to full sports participation, so that life after joint injury is full of potential joy. Watching them return is the thrill of the sport of orthopaedics.