What is New in the PCL?

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is injured when the knee is driven backwards onto the shin bone. This often occurs in dashboard impacts and from certain falls. Left alone the knee becomes unstable, wearing out the inside tissues. Here is what is new.

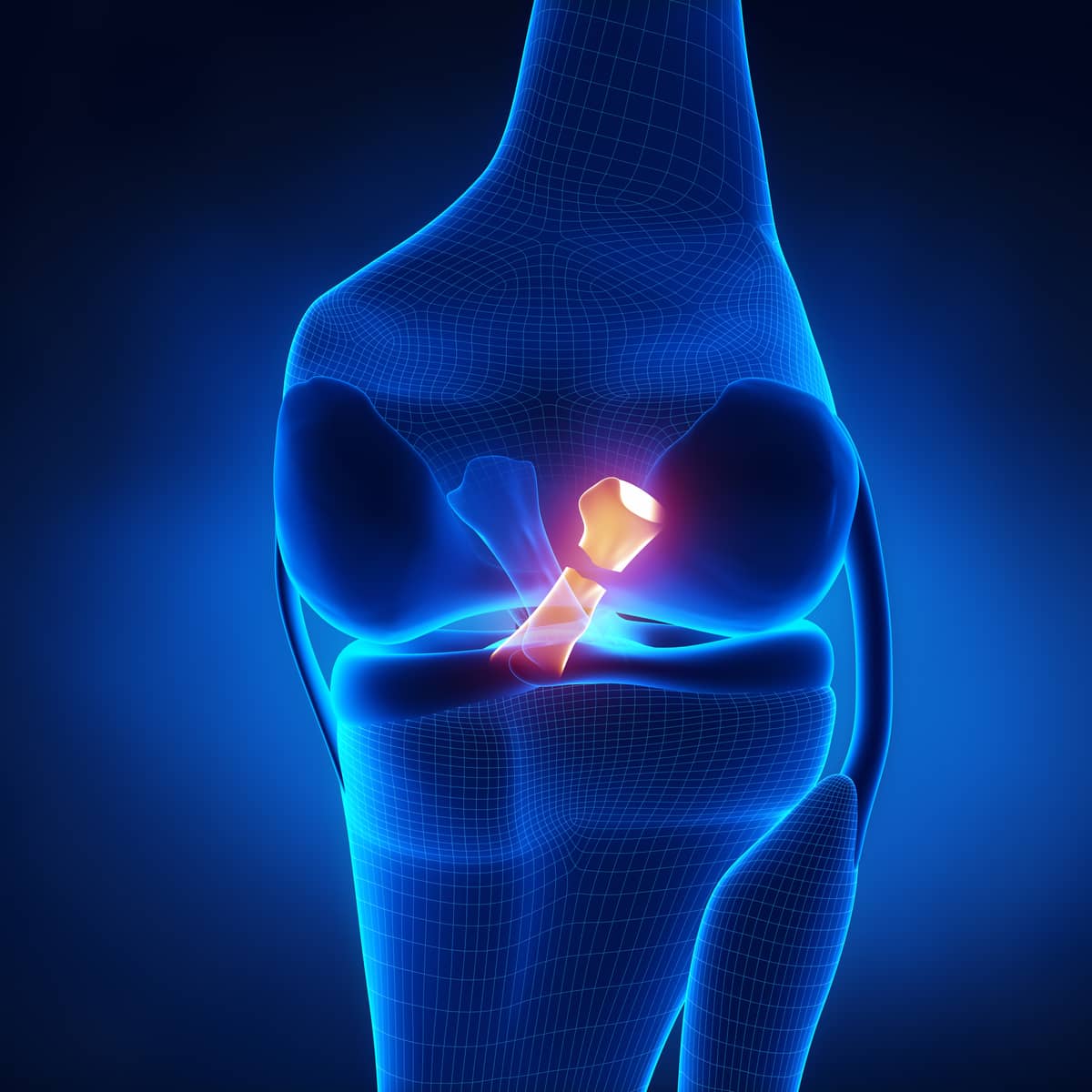

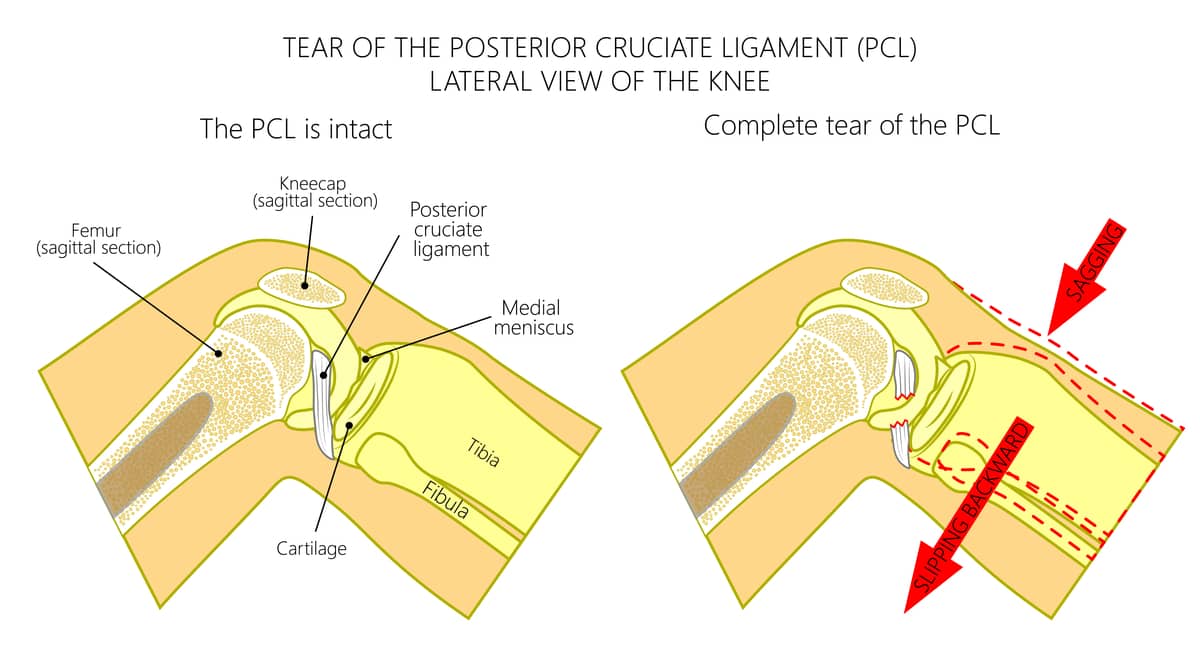

The posterior cruciate ligament stretches from the inside the femoral notch in the middle of the knee to the back of the tibia. It crisscrosses the anterior cruciate ligament. Both are crucial in permitting normal tracking of the ends of the bones on the meniscus cartilages. When the PCL is torn, the tibia is freed of its “guide wire” and permitted to track independently—and sometimes wildly—leading to wear and tear of the joint surfaces, and arthritis of the medial or inside of the knee.

In the past, people were often counseled to just live with their PCL tear. This advice was based on several factors: first, the damage from PCL instability often took years to show up in the knee; second, the surgery to repair the PCL was fraught with complications; finally, the PCL is a broad, strong ligament and until effective donor ligaments were available, the practice of robbing one part of the patient to rebuild their PCL was merely trading one injury for another.

Today, everything has changed for the better. We now understand that, over time, PCL injuries are usually fatal for the knee and must be treated—the sooner, the better. This is because the malrotation slowly stretches out the ligaments on the side of the knee, so much so that almost every chronic PCL I see requires not only a PCL reconstruction but augmentation with a ligament on the side of the knee (i.e., an extra articular reconstruction) to adequately stabilize the joint.

The initial diagnosis of a PCL tear is made by a physical exam. Next, an MRI identifies where in the ligament the tear has occurred. Occasionally, early partial tears can be identified and repaired. But most often the ligament is significantly ruptured and must be replaced.

The donor tissues available today are superior to those used before. To replicate the PCL, the quad tendon allograft—which is thicker than the patellar tendon and much stronger than the Achilles or any hamstring combination—is our go-to tissue. We augment this tissue with growth factors and secure the graft with solid, resorbable fixation devices that are unlikely to fail. Additionally, our knowledge of the PCL anatomy and its insertion points has advanced. We now have a far better understanding of where the surgeon should place the new ligament and how to adjust for each patient’s individual anatomy. The rehabilitation programs have advanced as well. By using stronger ligaments and fixation devices, the need for PCL braces has largely been abandoned. When repair is backed up with the extra articular reconstruction, the risk is of too tight a knee, rather than too loose. Therefore, early full weight-bearing—focusing on range of motion, followed by strengthening exercises—has replaced the crutches and braces of old.

PCL reconstruction still faces the same dilemma as ACL reconstruction in that that it takes up to a year for the tissues to remodel. This includes the ingrowth of new blood vessels, new collagen formation, and new cells that recreate the patient’s own tissue over time.

Ultimately, the tissue gets stronger with this remodeling. We are working to accelerate that process. To this end, we are developing advanced growth factor injection combinations to see if we can recruit the body’s own stem-cell-derived self-repair cells to induce early, strong new collagen formation. Our research is also focused on reducing the muscle atrophy we see in patients following these major ligament injuries and subsequent surgeries. This work is in progress and will continue to improve, with the goal of diminishing the disability from any injury or surgery.

Ask an athlete what was the worst thing about their knee injury; it is rarely the pain. Most often it is the muscle loss and the time it took to return to sport. As athlete-surgeons, along with our rehabilitation team, we deeply sympathize and mourn every day of lost sports activity—from our own injuries and those of our patients.

Dr. Stone explains the consequences of ligament injuries left unrepaired