Change Comes Slowly: ACL

Hear From Our Patients

ACL Surgery Revision Reconstruction Patient 6 Years Post-opThe anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) continues to be ruptured at alarming rates. Treatment has evolved, but only for some surgeons. Here are some controversies from the most recent international meeting, ISAKOS (International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery, and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine) in Munich 2025.

Repair and replacement of the ACL is one of the most commonly performed and researched procedures in all orthopaedic practice and literature. One would think the problems have been solved and the practices universally followed. The reality is dramatically different.

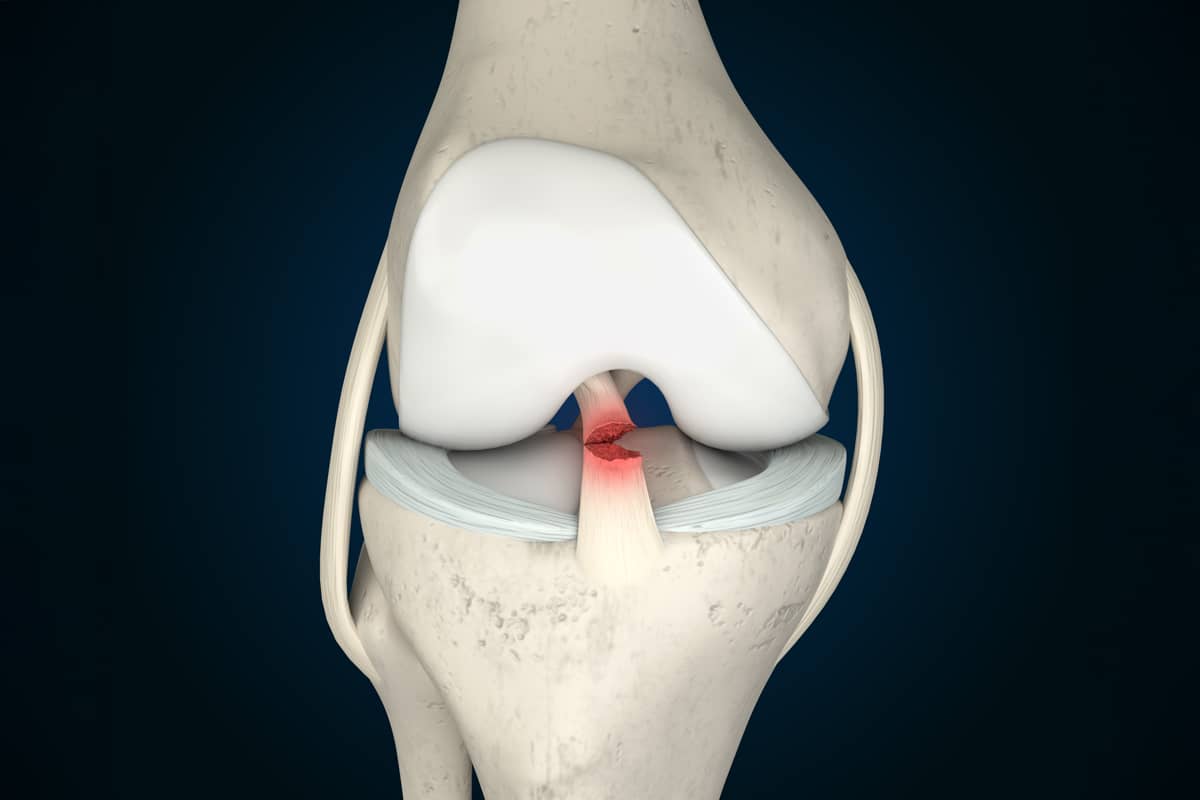

The anatomy of the ligament has been clearly shown by Smigielski (2016)1 to be a ribbon extending from the femur to the tibia, which twists with bending and extending the knee. Some surgeons, strongly influenced by commercial companies eager to sell their devices, argued for years that it was a two-bundle structure that could only be replaced accurately by a two-tunnel (and therefore double the number of fixation devices) surgical technique. The importance of anatomical replacement is now more widely understood.

Primary suture repair rather than replacement of the torn ACL is preferable only with a relatively rare type of ACL injury. When the forces are great enough to tear the ligament, most of its internal structure is severely damaged. Suture repair of only the top part, even with augmentation by artificial bands, occasionally (but not yet reliably) results in a stable, well-healed ligament.

Companies with new devices, however, encourage surgeons to repair more ligaments and add suture augmentation devices, since the short-term results in selected ligaments are often excellent. In our own study of 50 ACL primary repairs, only women over 35 years of age did well. The younger, aggressive males all failed. This is true in most of the ACL repair studies conducted in the past. It remains to be seen if the long-term results of repair plus device augmentation versus reconstruction will hold up.

Because of these findings, most ACL injuries lead to a ligament replacement (called reconstruction) rather than a suture repair.

Which tissue to use to replace the ACL remains in debate. The results from the hamstring tissues versus the patella tendon tissues do not appear to be too different, especially now that almost all ACL surgery is augmented by extra-articular reconstruction. Long-term weakness of the hamstrings leads many surgeons to avoid their harvest for skiers and other athletes. Long-term patella femoral arthritis, either from the original injury or from the harvest of the patellar tendon, leads some surgeons to avoid the patellar tendon harvest. That debate has now been further confused by the use of the quadriceps tendon: a thicker source of tissue than either of the other choices, which can be harvested with little apparent harm to the knee. But a failure rate of 10% to 20% plagued all surgeons who truly follow their patients. And the results were even worse for young female athletes. ACL surgery, despite the graft choices, is still nowhere near perfect.

The argument about the extra-articular reconstruction is this: When the ACL is ruptured, the tissues at the side of the knee are often also injured, but not fully identified by a physical exam and often missed on an MRI. By strengthening the tissue there with either:

- a reefing of the iliotibial band as was common in the 1980s;

- a posterior lateral reconstruction described by Larson (1988)2;

- by looping a portion of the band under the lateral collateral ligament as popularized by Sonnery-Cottet in Lyon (2016)3; or

- adding a graft to reinforce the anterior lateral ligament complex, surgeons have the potential to reduce the ACL failure rate to less than 5%.

This extra articular procedure most likely should be performed with every ACL repair or reconstruction surgery, as the complications of it are tiny and the benefits are clear from the large outcome studies published. Yet adoption remains slow.

The debate over the use of allograft or donor tissues remains suppressed due to the lack of availability in Europe and Asia, cost issues in the US, and some studies indicating a higher failure rate than when the patient’s own tissues are used.

In our biased view, however, the results are no different when we use an allograft from a young donor versus an autograft, and the addition of the extra articular procedure most likely will even out all the results to low numbers of failures. We don’t like weakening one part of a patient’s knee to rebuild another. We also want to avoid both the patella femoral arthritis from the patella tendon harvest and the weakness from the hamstring harvest. However, we remain in the minority of surgeons who use donor tissues all of the time.

Xenograft tissues from pigs are off the market until further funding, even though they represent a solid solution to the lack of availability of donor tissues in most of the world. Artificial ligaments failed miserably in the past, and though some are being used as splints or accessories to ACL reconstruction, they are more likely than not to be problematic due to stress shielding of the natural tissue and breakage of the artificial fibers over time.

While the ACL remains a rich source of research and opportunity for improvement, getting surgeons to read the literature, attend national and international meetings, resist corporate influence, and adopt the best science is still a challenge.

References

- Śmigielski R, Zdanowicz U, Drwięga M, Ciszek B, Williams A. The anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament and its relevance to the technique of reconstruction. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(8):1020-1026. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.98B8.37117

- Sidles JA, Larson RV, Garbini JL, Downey DJ, Matsen FA. Ligament length relationships in the moving knee. J Orthop Res. 1988;6:593–610. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100060418.

- Sonnery-Cottet B, Lutz C, Daggett M, et al. The Involvement of the Anterolateral Ligament in Rotational Control of the Knee. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1209-1214. doi:10.1177/0363546515625282

ACL Reconstruction Surgery Explained & Picking The Right ACL Graft

Dr. Stone shares the innovations in ACL reconstruction that lead to more successful patient outcomes and return our patients to the activities they love.