ACL Repair vs. Reconstruction: Here’s the Latest

Hear From Our Patients

ACL Surgery Revision Reconstruction Patient 6 Years Post-opAnterior cruciate ligament (ACL) primary repairs are having a moment in the sun. A few recent studies have indicated that they work. But do they? And if so, when? What are the risks and benefits of ACL repair vs. reconstruction? Here are answers to the common questions we are hearing.

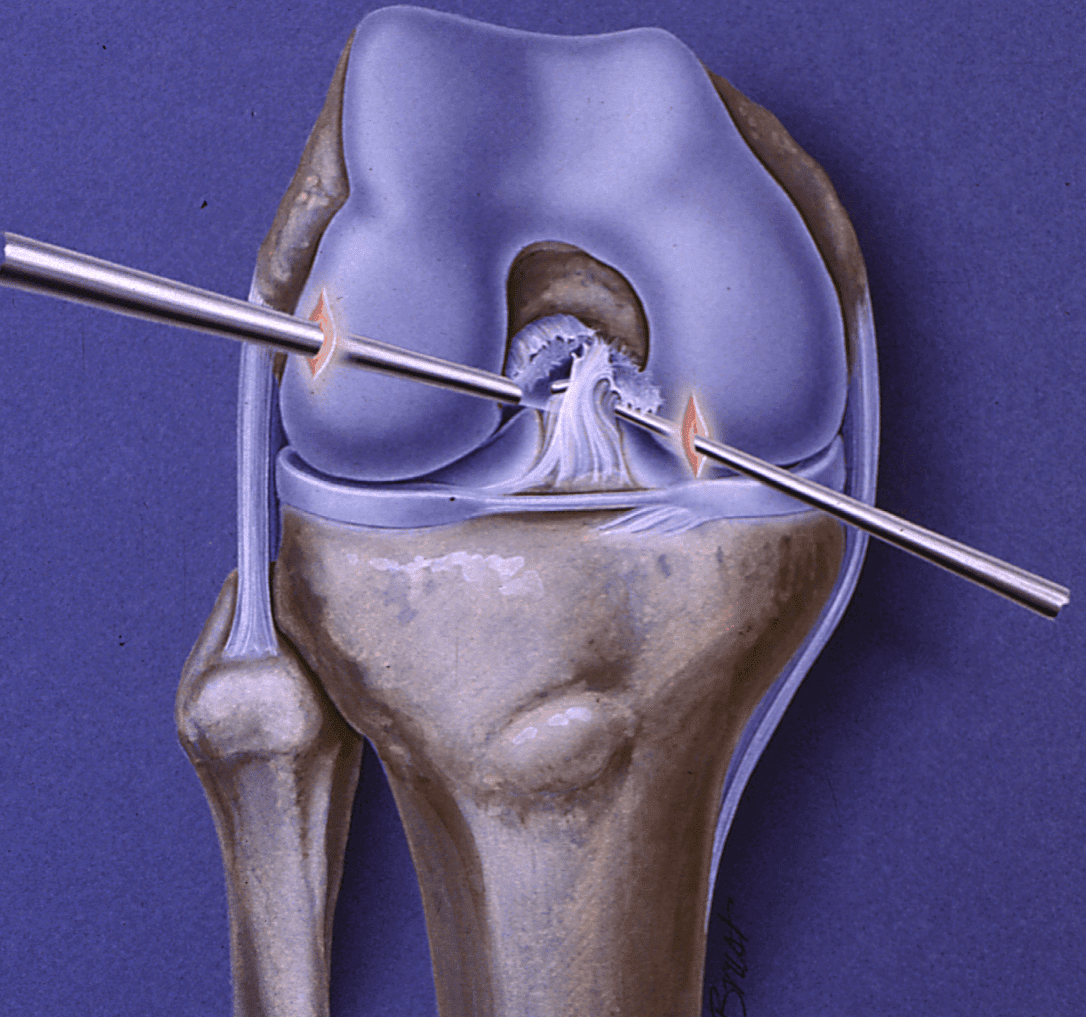

The ACL is the key guidewire for the knee, extending from the back of the femur to the top surface on the front of the tibia. It controls anterior displacement of the tibia. Most ACL injuries, unfortunately, involve rotational movements as well as forward and back translational displacements. This causes the ligament to rupture much the way a rope does, with fraying of the internal components as well as at the attachment points to the bone.

Efforts to suture back the torn fibers have been a holy grail of ACL repair for decades. Certain types of very mild tears—primarily from the insertion point on the femur and generally in older athletes—healed well after suture repair. However, the vast majority of torn ACL repairs did poorly. This was true despite the addition of growth factors, supportive sutures, and augmentation bands of polyester and other materials. The failures occurred because the ligaments were fatally damaged by the initial injury and the primary repair of the top of the ligament was not enough to stabilize the knee.

Additional causes of ACL repair failure involved the fact that the rotational injuries damage more than just the ACL. The tissues on the side of the knee, from the meniscus to the collateral ligaments (including the soft tissue corners of the knee) are also frequently stretched or torn during the initial injury. These must be repaired or the ACL will stretch out during the healing period.

And just as with ACL reconstruction, if the repair does not hit the normal ACL insertion point, the biomechanics of the knee are not restored and the repair fails.

Recently, collagen scaffolds have been added to the repairs in the hopes that the additional collagen will improve the outcomes of ACL repairs. There is initial optimism but—as with the long history of ACL repairs—the failures usually present after patients return to full sports, usually after a year or two. Early results are simply not predictive.

Growth factors and stem cell recruitment factors have been in vogue during the last few years. These are anti-inflammatory, anabolic, and help direct the healing response by recruiting the body’s stem cell-derived progenitor cells. Though they should be effective in accelerating healing from an ACL injury or surgery, the results are not in yet on how much faster this may be. We do see that in patients struggling with range of motion or swelling in the postoperative period, an injection of growth factors plus hyaluronic acid (the natural lubricant of the knee) appears to help reduce symptoms and improve their motion.

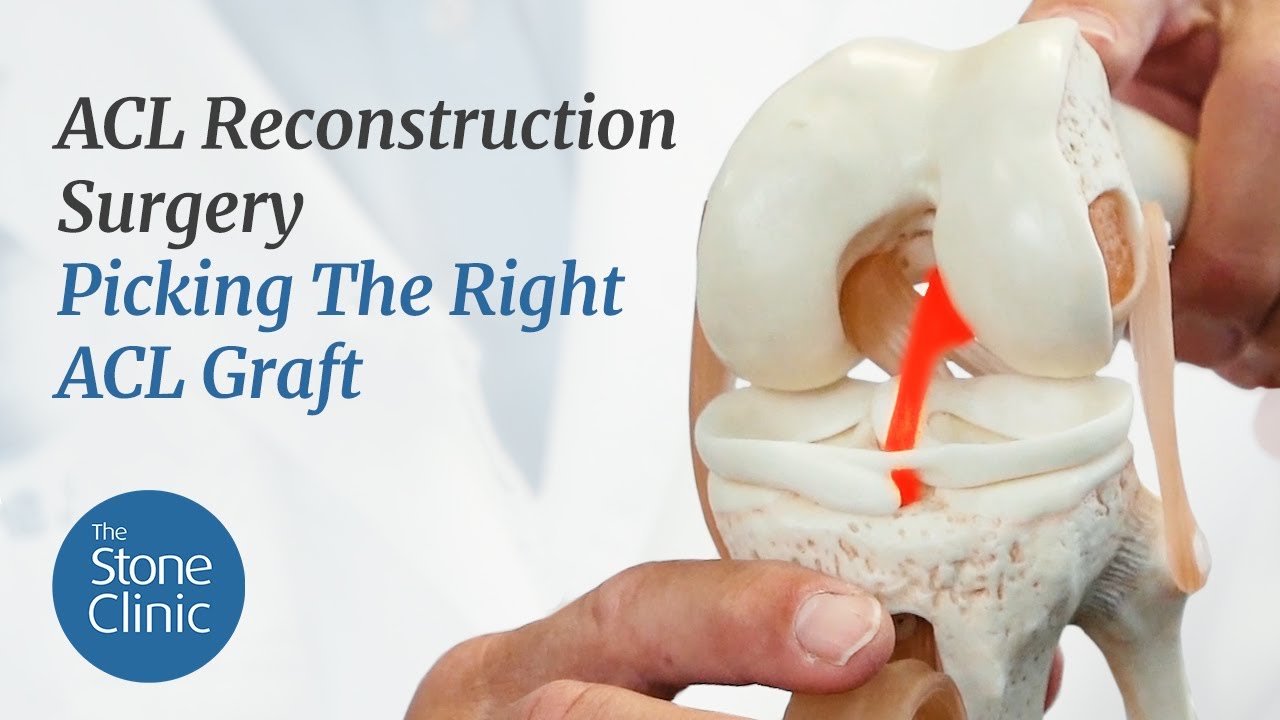

On the positive side, when a repair works, the knee feels more normal than if reconstruction is performed. Reconstructions involve drilling holes in the femur and tibia and harvesting either the patient’s own patellar tendons or hamstring tissues. (Our preference is to use a donor quad tendon). Any reconstruction is a bigger surgical adventure and has a longer recovery time than a primary repair. However, very few anterior cruciate ligament tears are ideal for primary repair. Many surgeons believe that ACLs that do undergo primary repair would have healed well on their own. The ideal candidate for primary repair is still a small tear of the ligament, located at the insertion at the femur where most of the ligament remains attached.

Patients always have the choice to have their ligament treated with surgical repair or reconstruction. As stated previously, however, very few ligaments are ideal for repair alone. At The Stone Clinic in San Francisco, with our long history of both repair and reconstruction, we have found that the most successful repairs are for small partial tears in patients 50+ years of age, while the best reconstructions use an allograft of quadricep tissue from a young donor.

But there is still room for improvement in all of these procedures and our research and that of others are aggressively pursuing these advances.