Change Comes Slowly: Total Knee Replacement

Hear From Our Patients

Back to Skiing on a Total Knee ReplacementIn medicine and surgery, it is said that progress comes one death at a time: The death of physicians. While not funny, friction in the system causes out-of-date thinking to persist and practices to be abandoned slowly. Here are some examples from the world’s largest orthopaedic sports medicine conference, held in Munich in June 2025.

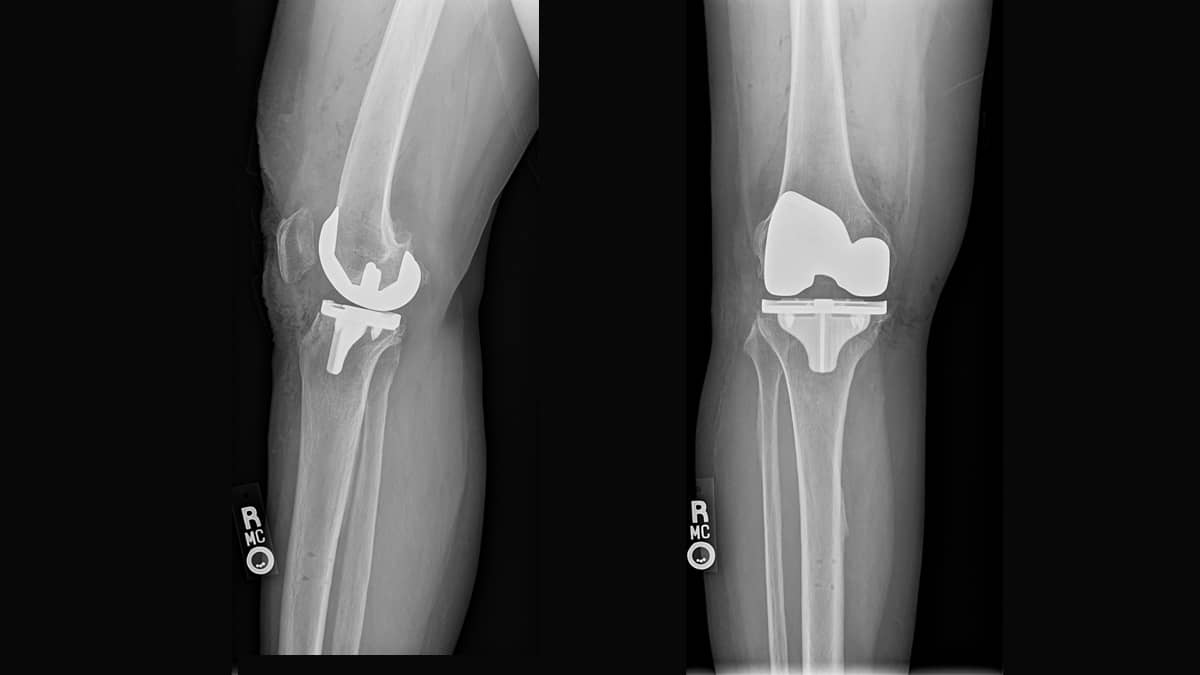

Artificial knee joint replacements are performed over 790,000 times each year in the United States alone and more than one million times worldwide (1, 2). For patients with severe arthritis in multiple parts of the knee, the procedure is a godsend, relieving pain and returning people to active lives. It comes, however, with a not insignificant failure rate—and is very difficult to salvage once it fails.

The story of total knee replacement began with the first designs in the 1950s and took a major leap forward in 1973 with the total condylar design and the merger of metal with polyethylene. Modular designs of the implants were introduced in the 1980s, with computer-assisted navigation in the 2000s.

Today’s orthopaedic surgeons are divided between those who do only artificial total knees; those who include partial knee replacements in their repertoire; those who also offer biologic knee replacements (i.e., replacing the meniscus, regrowing the articular cartilage and reconstructing the ligaments), and those who provide injections of lubrication and growth factors (PRP) combined with rehab programs to delay surgery. Their individual beliefs are very strong.

Here are some of the overwhelming biases presented by surgeons on the panels at the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) meeting in Munich in June 2025. My own approaches follow.

Panelist: “I rarely inject knees, just replace them. And if an injection is used, I only inject cortisone.”

My bias: There is overwhelming data that injections of hyaluronic acid (lubricant) and an anabolic (PRP) and other growth factor concentrations provide pain relief for many patients with arthritis. Relief can last up to 18 months, according to our own prospective double-blind trial and those of others. Cortisone can also provide pain relief, but damages the surrounding tissues and leads to a higher incidence of infection if surgery is performed in the post-injection window.

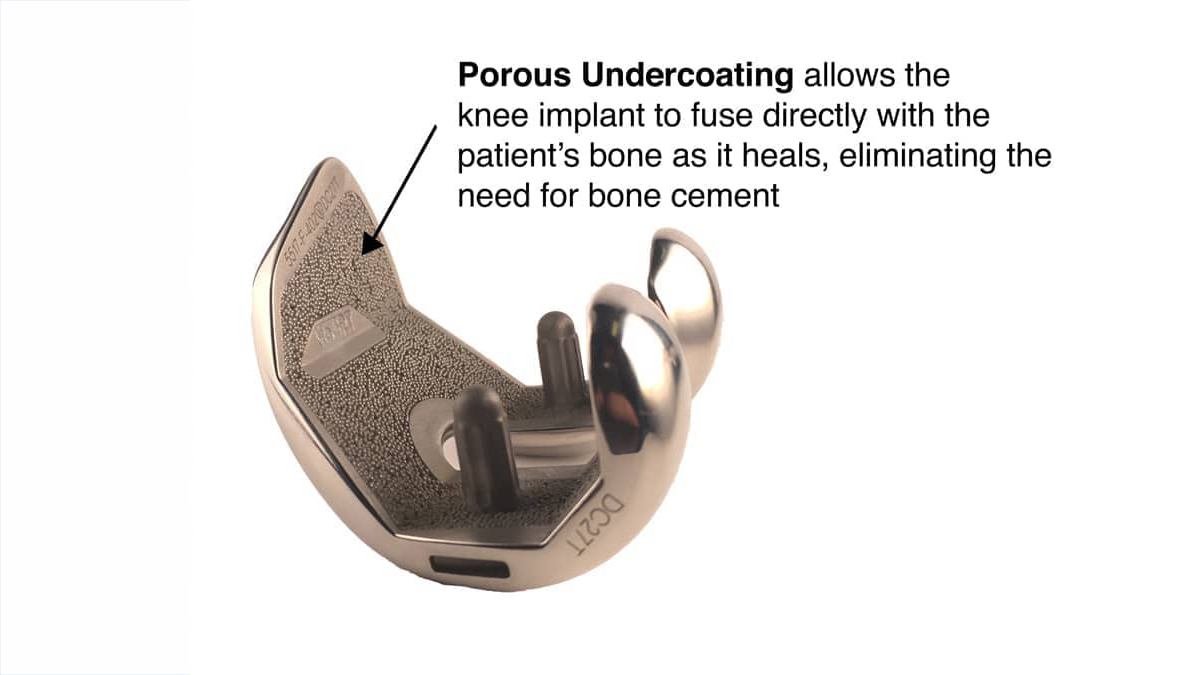

Panelist: “I only do cemented total knees, no matter the age of the patient.”

My bias: Uncemented total knees, when performed with the precision of a robotic arm, permit patients to go back to full sports without the worry of loosening the cement interface. In the osteoporotic bones of the elderly, the cement hardens with a process that produces heat. This kills some of the surrounding bone, leaving a potentially weak cement-to-bone interface. It does not improve the survivability of the implant. Older people have the ability to heal their bones if given the right conditions.

Panelist: “I rarely do a partial knee replacement and almost never on the lateral side.”

My bias: Many patients wear out only one part of their knee. Why sacrifice normal tissue? Partial knee replacements feel more normal than total knee replacements, recover more quickly, and return to full sports faster. Lateral partial knee replacements are the most difficult to do (without a robot to ensure rotational alignment) but provide the most satisfaction. If properly aligned, they rarely—if ever—fail.

Panelist: “If the patient has some patella arthritis, I always do a full knee replacement.”

My bias: Partial knee replacements of the patella femoral joint have evolved. With 3D modeling by CT scan before surgery, the implants can be placed perfectly, providing full pain relief. We are testing only resurfacing the trochlear groove, without using a patellar button. This further speeds the recovery, reduces the risk, and improves the range of motion.

Panelist: “I always replace the patella with a plastic button when I do a full knee replacement.”

My bias: Replacing the patella or leaving it alone, independent of the amount of arthritis on its surface, has been shown in multiple large registry studies to have equivalent outcomes. Patella resurfacing has one of the highest incidences of complications, so we rarely add this step to our total knees. We have applied this research to isolated patella femoral replacements, and we now resurface only the trochlea in selected patients.

Panelist: “I always use a tourniquet in my surgery.”

My bias: Tourniquets have been repeatedly shown to produce post-op muscle pain, with muscle and nerve injuries. The drug tranexamic acid (TXA), if given an hour before surgery, dramatically limits bleeding during surgery and reduces post-op swelling and pain with no significant increase in blood clotting risk. So why not use this “chemical tourniquet” rather than a physical one?

Panelist: “I keep my patients in the hospital post-op to monitor them and for pain control.”

My bias: Newer forms of long-acting gel- and fat-based anesthetics (Syn Relief and Exparel) can reduce or eliminate post-op pain for 48 hours or more. If preemptive anesthesia techniques are used (including patient education, injection of short-acting anesthetics before any incision, efficient surgery, and a drug combination of post-op long-acting anesthetics with the addition of ketorolac [Toradol] or NSAIDs plus Tylenol), most patients have very little pain. Almost all go home within an hour of the end of the surgery. Many patients, even 80-year-olds, also use THC and CBD gummies to reduce any need for narcotics or sleeping medications postoperatively. We cannot yet prescribe them legally, however.

Panelist: “I don’t prescribe physical therapy. I just give the patients exercise instructions to do on their own.”

My bias: Tragically, knee replacement surgery has complications, both in the immediate post-op period and—in as many as 50% of patients—as long as ten years later. Many of these complications can be reduced or eliminated by adopting different approaches. The most important one, in my view, is to help the patient see their surgery as an opportunity to become fitter, faster, and stronger than they have been in years.

Without knee pain, this can become a reality. Immediate post-op physical therapy, with hands-on massage to treat swelling and exercises to both increase range of motion and increase the sense of wellness, dramatically improves our outcomes. Raising the heart rate on a stationary bike or rowing machine, starting core exercises, blowing off the anesthetics, and working out with a therapist day one post-op patient starts the process of seeing yourself not as a patient in rehab but as an athlete in training. We encourage daily physical therapy, fitness training, and exercise for all patients until they have achieved the range of motion goals set out for them, improved their gait, and pushed forward their fitness. This goes on for a lifetime, which is why we ask our patients to return multiple times in the first year and then annually, when possible, for fitness assessments and optimization of their program. Being a “patient for life” is not a pejorative; it’s recognition that we are all degrading — and exercise is our best antidote.

Panelist: “My outcomes are excellent.”

My bias: How do you know? Most surgeons do not follow their patients after the immediate post-op period. Patients with problems often go to other doctors.

Knowing the bias and the outcomes of your doctor and/or surgeon helps you, the patient, make an informed decision. At the end of the day, what works well in their hands is an important factor. However, most doctors do not know their own data, as they do not conduct outcome studies. This can and must change. Nearly all patients carry cell phones, and outcome study apps are widely available. It takes only curiosity and desire to find out whether or not what you think is true is actually true. Even as a physician, what you believe today—if you dive deeply and openly into the literature and follow the outcomes of your patients—will evolve to help you think and act better tomorrow.

References

- Ray L. Joint replacement surgery. American College of Rheumatology. 2025. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://rheumatology.org/patients/joint-replacement-surgery.

- Dossett HG. Machine Learning: The Future of Total Knee Replacement. Fed Pract. 2022;39(2):62-63. doi:10.12788/fp.0224

Our Approach to Total Knee Replacement

While we are biased to replace knees biologically, here's how recent advancements in robotic-assisted surgery technology give Dr. Stone unparalleled accuracy in placing knee replacement implants, allowing for a quicker recovery time, better range of motion, less pain medication, and greater durability for demanding activities—including running.