First Time Shoulder Dislocations

The first time the shoulder dislocates is memorable. It hurts. What to do?

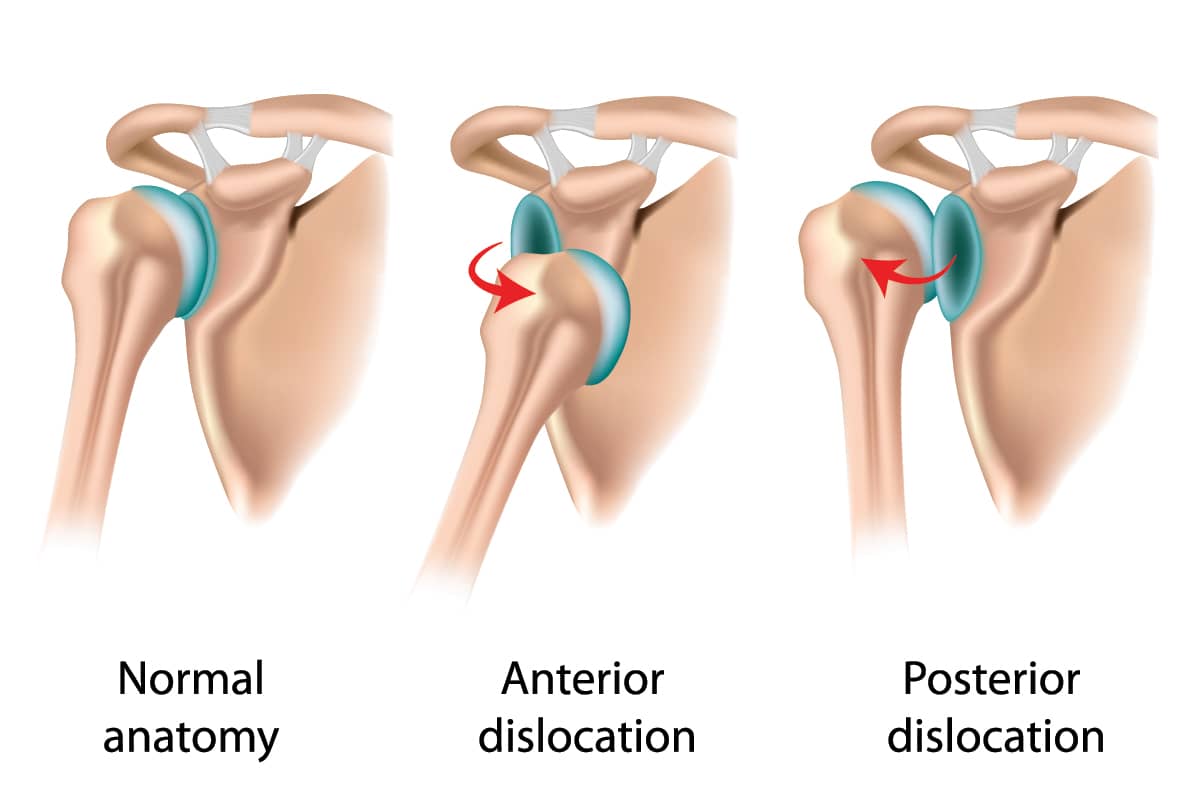

The upper end of the arm (the humerus) sits in a shallow socket (the glenoid). It is held there by a circular ring of tissue (ligament labrum complex), similar to a gasket in a hose. When torn, it permits the humerus to slide off the glenoid face, and a feeling of subluxation or instability is noted. From that point on, the shoulder dislocates more often. For our overhead athletes, or those in challenging environments such as whitewater kayaking, backcountry skiing, or surfing, a repeat dislocation can be a life-threatening event. But for all active people, a repeat dislocation is a daily risk. The more the shoulder dislocates, the more damage is done to the cartilage surfaces, and the greater the likelihood that an arthritic joint develops.1

The old advice to “let it heal in a sling and see what happens” has been extensively studied. It doesn’t work for young people. Recent publications demonstrate recurrent dislocations (89.5% in the non-operative group; 27.8% in the operative group) with a better return to the same level or better in sports (82% in the operative group).2

Moreover, the success rate of surgery declines after multiple dislocations.3

Though injections of PRP plus HA and other growth factors often make the injured joint feel better, they have never been shown to regenerate or repair torn tissues. That said, we do find the injections helpful for patients who must wait for surgery. They reduce symptoms of pain and inflammation and, for patients in the post-op period, they reduce the symptoms and may accelerate healing. Hopefully, we can improve the injections enough so that the likelihood of arthritis will be diminished. This is a hot topic of research at this time.

Clearly, early surgical repair of a dislocated shoulder should be considered. Most of the time, the repair works well, and our athletes return to full sports after a few months. One question that arises is, “Why are there still so many recurrences, even after repair?” One answer is that these patients are often in risky environments where shoulder injury is common. A second reason is that our repair techniques, while good, are not perfect. Third, the amount of time it takes for repaired tissues to heal and regain strength is too long—and sometimes never. The field of biologic augmentation is nascent, but holds promise for a future in which we can manipulate the healing process to accelerate not just healing, but strengthening of the damaged tissues.

This is our goal at the Stone Research Foundation, and our thought process with each and every tissue that we repair: that we can do each one a little better than the last.

References

- Brophy RH & Marx RG. Osteoarthritis Following Shoulder Instability. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 2005;24(1):47–56. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2004.08.010

- Pougès C, Boutry M, Maynou C, et al. Arthroscopic Bankart Repair Versus Immobilization for a First Episode of an Anterior Shoulder Dislocation Before the Age of 25 Years: A Randomized Controlled Trial With 6-Year Follow-up. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2025;53(10):2289–2297. doi:10.1177/03635465251350151

- Marshall T, Vega J, Siqueira M, Cagle R, Gelber JD & Saluan P. Outcomes After Arthroscopic Bankart Repair: Patients With First-Time Versus Recurrent Dislocations. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;45(8):1776–1782. doi:10.1177/0363546517698692