The Changing Approach to Rotator Cuff Repair

The rotator cuff, a group of four muscles and tendons located in the shoulder, is prone to a variety of injuries that can cause pain, weakness, and loss of motion in the arm. In this interview with Jeff Greenwald, Dr. Stone talks about the fine points of rotator cuff repair and why non-surgical options are becoming more commonplace.

Shoulder surgery seems to be something of a moving target when it comes to orthopaedics: if and when to operate, what techniques to use, and how to rehabilitate the injury after surgery. The care required to repair and recover from a rotator cuff injury seems equal parts art and science.

Dr. Stone: True. But I do think that our understanding of rotator cuff injuries is evolving, in terms of both surgical and non-surgical treatments.

How so?

Dr. Stone: What we're finding now is that small tears, incomplete tears, and nerve impingement alone are far more often successfully treated non-operatively than we ever thought before.

If we give people a chance to heal and create the biologic environment for healing—often by adding growth factors and lubricants to accelerate the process, and working with physical therapists to restore normal mechanics of the shoulder—they can often avoid surgical intervention. Whereas in the past, we thought they always needed it.

Many people over the age of 50 have combinations of rotator cuff tears, labral tears, and mild to moderate arthritis. Yet most of them are essentially asymptomatic, meaning they don't even know they have these issues.

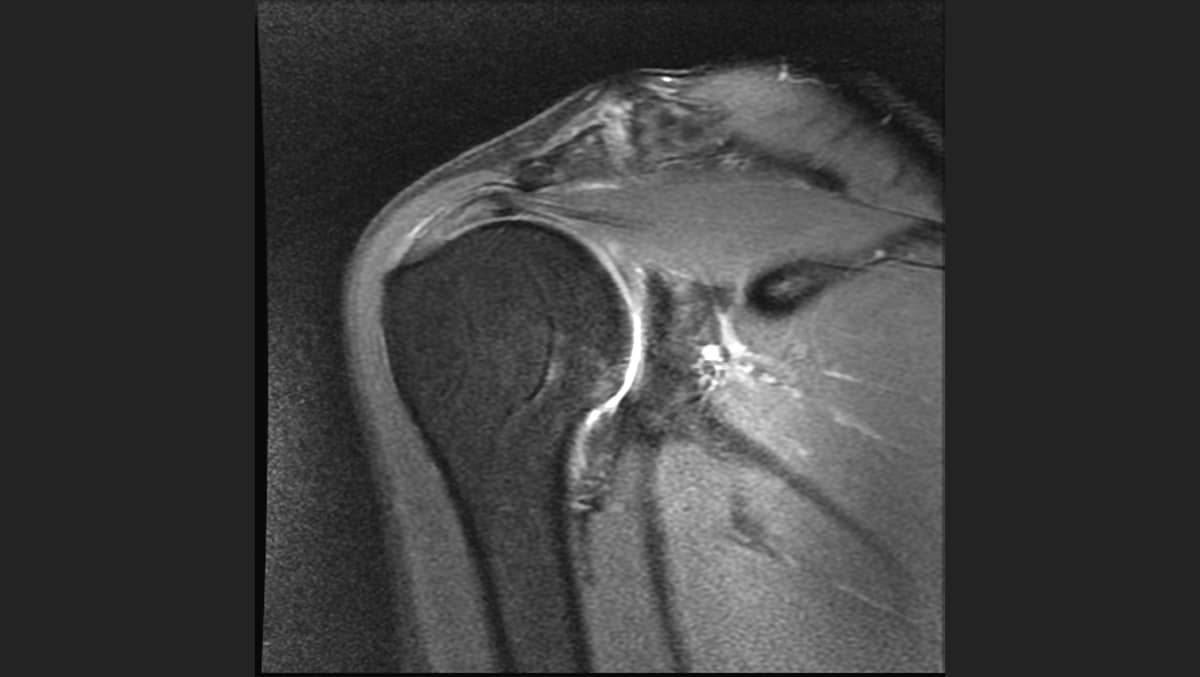

Once diagnosed, usually after a fall or an overuse injury (36 holes of golf rather than 18, a hard tennis match, or a Pickleball tournament) the workup with X-rays and MRIs often show both the acute and chronic damage. Then the decisions about care begin.

If the patient is not in a rush, the vast majority of these presentations are now treated initially with anabolic and lubricating injections, in combination with a rehabilitation program.

What key factors in treating a rotator cuff injury will determine how normal a patient's shoulder will feel after their recovery?

Dr. Stone: Part of it is the degree of tearing and the degree of muscular dysfunction. Some people with big tears have very little pain and very little dysfunction, muscularly—while other people with a small tear have a lot of pain and dysfunction. The people who are pretty dysfunctional and in pain may need to have earlier repair. But even those patients often have better surgical results after a period of injections and rehabilitation as the shoulder inflammation quiets down.

Rotator cuff surgery has a long and uncomfortable recovery period. It’s easy to understand why some people opt for a non-operative approach to rotator injuries through physical therapy.

Dr. Stone: True. And there remains a huge debate around early motion and rehabilitation exercises versus “locking them up” in braces and slings. In general, we are advocates of early motion after most repairs.

How many injections are permissible? Is there a limit?

Dr. Stone: There’s a limit on corticosteroid injections, but we almost never use corticosteroids around the rotator cuff anymore. That’s because it damages the tissues, and increases the risks of infection and tendon rupture. What we use is a combination of growth factors from platelet-rich plasma (PRP) plus hyaluronic acid.

The agents in PRP have a multitude of effects. They are potent anti-inflammatories, stimulate the lining of the joint to produce more lubrication, and recruit the body’s own stem cell-derived progenitor cells to migrate to the site of injury and modulate the healing response. The recruitment effect is so potent that we no longer inject cells directly into the site of injury, since the body has billions of these progenitor cells which can be mobilized.

Are there any rotator cuff injuries that absolutely require surgery?

Dr. Stone: I think that in the case of complete rotator cuff tearing, dysfunction, and pain, patients will usually do better with a surgical repair than not. There are other instances when we would push earlier for surgery—such as instability, tearing of the subscapularis tendon, fresh retracted tears, and other situations. But I think that's a good generalization.

Is there a standard approach to surgical repair or is it different in every case?

Dr. Stone: In my view every case and every patient is unique. There is room for lots of creativity and surgical technique improvement as well as customization of the rehabilitation program to the goals of the patient.

Is there something unique about the way the Stone Clinic treats rotator cuff repair?

Dr. Stone: Yes. We bring a lot of teamwork, brain power, and creativity to different types of injuries.

For example, one very common injury in pitchers and throwers is a slap tear, where the superior aspect of the labrum and bicep is torn off the bone. The way that injury is repaired determines whether or not the patient regains their full range of motion. Understanding that patient's tissues—where their repair should be done, where it should not be done, how tight to make it, and how early to start rehabilitation (which, in our view, is almost always on Day One) determines a lot about the patient's outcome.

Every surgeon, I think, looks at tissue through their own lens and their own bias. At The Stone Clinic, we're quite tissue-preserving, with a bias towards recreating normal anatomy whenever possible and helping patients return to life and sports better than they were before they were injured.

For those who do choose to opt out of surgery, what kinds of activities should be avoided?

Dr. Stone: Things that cause pain are good things to avoid—such as lifting with bad biomechanics or reaching behind you with the injured arm – say, to get something from the back seat of your car. Pain and persistent weakness are to be avoided and if they are not resolving, treated.

It is also important to be diligent about movement—because permitting the shoulder to become stiff is also a good thing to avoid.

Let’s conclude with a few words about my own case. I have been diagnosed with a complete tear and two minor tears in my rotator cuff. Still, I have pretty good range of motion—and I'm doing physical therapy every day. One orthopaedic surgeon told me that 80% of the people he treats can, through diligent PT, train the nearby muscles of the shoulder to take over the functions of the torn muscles. Do you think it advisable that most people with rotator cuff injuries—including complete tears—at least try a less invasive approach before opting for surgery?

Dr. Stone: Again, it depends on a wide range of factors. These include the patient's physical presentation; how much dysfunction they have; what the X-rays look like in terms of arthritis; what the MRI looks like in terms of muscle-wasting or atrophy; and how much inflammation exists in the tendon.

There are a huge number of things to consider. And it's very important to think these things through with your surgeon—and your physical therapy team—in order to make an informed decision and establish a well-coordinated plan.

Here's How One Patient Recovered from a Cuff Tear to Swim the Alcatraz Channel during her Annual Follow-Up Appointment

Experiencing Undiagnosed Shoulder Pain? Use our Shoulder Pain Symptom Checker to better understand your symptoms and find out possible injury conditions.