The Too Flexible Athlete

“Stretch, stretch more, do yoga, do Pilates,” our trainers encourage us in a never-ending litany. Our stiffness is hurting our backs, our knees, and our performance. But what about the too flexible athletes? Not the contortionists; I’m talking about the loosey-goosey amongst us. Are they better off than we are, with our minor stiffnesses?

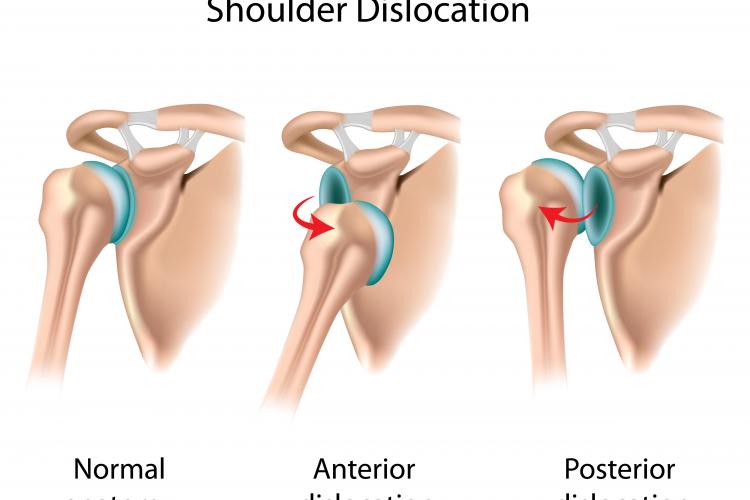

Tissue tightness is both a curse and a blessing. Our tissues are made up of collagen, the most ubiquitous protein in the body. When warmed up or stretched regularly from training and exercise, these tissues permit our joints to move in defined patterns: to run, lift weights, and dance without injury. If they are too tight, we are unable to engage the entire range of motion of our joints. That’s when we overuse our muscles to achieve our goals and get injured. But when too loose, our joints slide in and out or easily dislocate.

Only one in 5,000 of us has joint flexibility at the far end of the normal spectrum. A simple test to see where you are in the flexibility scale is to bend your thumb backward. If you can touch the bone in your arm, you are quite flexible. In addition to loose joints, you may have a range of presentations that go along with excess flexibility. These might include a high-arched palate, a heart murmur, the need to wear glasses, and a very tall height—all of which may be variants of genetic mutations, grouped under the name Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

At the far end of this scale are the patients who fit the full Marfan’s Syndrome description, which includes all of the above along with sometimes fatal heart conditions. But the most common visitors to my office are the Ehlers-Danlos type III patients, whose shoulders are so hypermobile that they dislocate with common sports activities—or even when they roll over in bed. (The ballet dancers I treat often come close to this level of flexibility, but usually without the joint problems.)

All collagen fibers have bridges between them called crosslinks. While it was once thought that the more crosslinks, or the stiffer the crosslinks, the stiffer the person; it is now understood that it’s the organization of the collagen fibers themselves that leads to the variations in the tissue behavior. After we’re born, we do not have drugs or therapies that can change the level of stiffness of the tissues.

What we can do is repair the damage once the joints dislocate. And while we’re there, tighten the tissues with seamstress tricks of making pleats in the excess tissue and, for some joints, adding donor tissues to augment the repairs. For the dislocating shoulders, we reef the loose capsule surrounding the shoulder all the way around, from the front to the back. For damaged knee ligaments, we add donor tissues to rebuild the ACL and reconstruct the corner tissues of the knee. The donor tissues are not initially plagued by the loose collagen structure, though over the years are most likely replaced by the patient’s own collagen with its genetically unique loose characteristics.

There are no DNA therapies, drugs, or magic on the horizon likely to change a person’s entire body makeup. So for those people with hyper-laxity, we emphasize fitness programs that not only strengthen their musculature—in order to catch themselves before an injury occurs—but also improve their coordination, balance, accuracy, and confidence.

While it may be a liability to have hyper-loose joints, the injury-producing events are often controllable (and the condition is fatal only in rare instances). One can look at this apparent liability as an opportunity to have more time playing—since you don’t have to waste time stretching. Many of my patients would gladly make that trade.